Setting goals is a common practice, whether shedding those extra pounds, improving our sleep patterns, dedicating more time to loved ones, or writing a substack post every two weeks. Yet, why do these resolutions often falter, leaving us in a perpetual renewal cycle?

It's essential to grasp the inner workings of human behaviour to understand how we can truly achieve our aspirations.

The Autonomous Nature of Humans

Human beings operate predominantly on autopilot, both mentally and physically. Our bodies and minds function as intricate machines, evolved to perform autonomously over time.

Physical Autonomy

Most of our body's energy is devoted to autonomous functions such as regulating temperature, digesting food, maintaining heart rate, and fueling brain activity. These processes are controlled by mechanisms inside the body that are not under our direct control. They are controlled by maintaining 'set points' with sensors and feedback loops, constantly adjusting to maintain preset levels, or "set points” encoded by genes or previous habits.

Our resolutions often revolve around these set points—weight, sleep, health, and focus—reflecting our desire to alter these programmed norms.

Mental Autonomy

Similarly, our brains function like efficient executive assistants, handling routine tasks without inundating our consciousness. We navigate through daily activities—like driving to work—mainly on autopilot, reserving attention for novel or threatening stimuli, with consciousness remaining unaware of most of what the brain is really doing.

The human brain uses the vast majority of its processing power of the brain for autonomous activities - like walking, breathing, and interpreting the senses (sight, smell, touch). Only a tiny proportion of the brain's capacity is available to us - and in this limited attention span, we can only process or remember very few things.

Think about your drive to work this morning. Did you have to focus on the details of the drive? Or did it pass by in a blur while you listened to music and planned your day? As anyone developing an autonomous vehicle would tell you, Driving requires tremendous processing power and attention, so how could you do it without focusing?

In reality, the brain focuses attention on what is new and potentially threatening. The first time you drove in your life, driving fell into this category. Your brain would be entirely concentrated on decoding all the signals streaming into your eyes and ears. You would read every road sign and look at every other car as a threat. You did not drive 'autonomously' the first time you drove. Over dozens of drives, though, your brain figured out 'how to drive' - and created a 'driving program' - physical neural pathways that enable you to repeat driving without needing to think about it. When you drive, your brain repeats the 'driving program' and a small 'alert program' that tells you if anything not in the normal 'driving program' comes up. If the car in front of you suddenly brakes, you will be alerted, and your attention will switch back to driving.

This mechanism enables you to perform very complex tasks on 'autopilot'. Our brains operate on the law of least effort or the path of least resistance. The most worn pathway is the easiest to travel.

Set Points

Inertia is the property of matter by which it continues in its existing state of rest or uniform motion in a straight line unless an external force changes that state. Everything has inertia.

Most systems have a set point, 'programmed,' and tend to default to it.

Inertia governs much of our behaviour, akin to the physical property of matter. Most systems, including our bodies, have set points, defaulting to programmed norms unless external forces act upon them.

When we act on our resolutions, we increase the deviance between the set point and actual status, and the body triggers autonomous reactions to return to the set point, taking into account the new level of activity.

Let's take an example of weight loss.

The human body is a highly complex system.

The resting metabolic rate consumes about 60% of the energy consumed in food (R.M.R.). This is the energy needed to keep the body functioning in a resting, awake and fasting state in a comfortable, warm environment. The Thermic effect consumes another 10%. This is the energy needed by the digestive system to process food. Only about 30% of our energy is consumed by physical activity.

The body has a metabolic 'set point'. It has a mechanism to measure the current level of fat in the cells at all times and tries to maintain it.

This explains why many diets don't work for long and can cause long-term damage.

Let's say your 'set point' is at 70 kgs. You usually consume 2500 Kcal of food energy. You start a crash diet at 1500 Kcal/day and lose 5 Kgs. Your 'set point' remains at 70 kgs. Your body will automatically find ways to slow down your R.M.R. (slower breathing, heart rate, lower body temperature, less inflammation, less energy to the brain, etc.). Before long, you are back at 70 Kgs, and now the set point corresponds to 1500 Kcal. Now you need to eat 1000 K cal to lose weight again.

To adjust your weight in the long term, you need to adapt your set point by creating new habits over a long period (and yes, one component of this is diet).

There are similar set points at work everywhere - how much you sleep, how you allocate time.

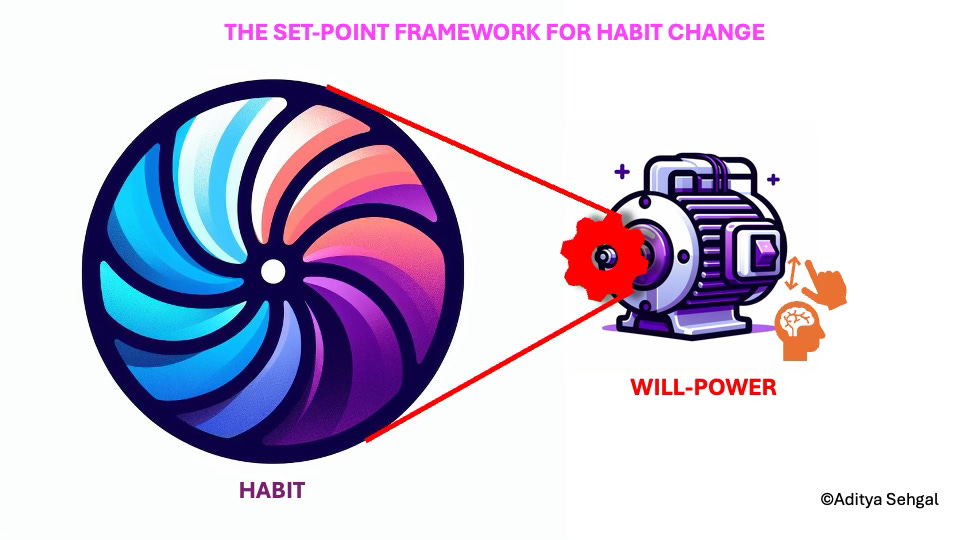

Think of a set point like a flywheel. It has momentum and tends to keep turning for a very long time.

The big question in habit change is: How can you change your set point so that the default systems' automatically' work in your favour?

Changing these set points requires establishing new habits—a gradual process involving consistent effort. These habits reshape our internal programming, akin to adjusting the momentum of a flywheel.

The Framework:

Use willpower (like a motor) to add momentum to a habit (flywheel) at regular intervals.

Over time, the momentum in the habit will become strong enough that it doesn’t need willpower anymore to drive it.

Willpower vs. Habit

We can only use willpower when we focus our attention, while our habits are automatic—what we do by default.

Our attention is a finite commodity, and the most pressing priorities or threats typically hijack it.

Over the long term, habit grinds willpower into dust. This is why most of our resolutions fail.

We start the year (and the resolution) full of gusto and willpower. As time passes, our attention gets diverted to the next shiny thing, and our habits take over. Before we know it, we are back where we started.

We must recalibrate our set points through habit formation to effect lasting change. This involves strategically using our scarce willpower to engrave new routines into our brain's neural circuitry, a process facilitated by consistent repetition.

Making lasting change

To make lasting change, we need to change our set points.

These set points can be physical or mental.

Set points can be changed by creating new habits.

Every skill exists as a circuit in our brains. And that circuit needs to be formed and optimised.

To create new habits, we need to engrave new 'programs' into the soft tissue of our brains.

To create these new 'programs,' we must use our willpower to repeat actions at a set schedule several times so that a physical change in our brains occurs and a circuit is created or strengthened.

The mechanism for making physical changes in the brain is suspected to be related to myelin. Think of the Axon (nerve cell) as a conductive wire. Myelin is the substance that coats the axon (think of the rubber sheath around a wire). Trying to create a new skill creates a connection of neurons—a new circuit.

To begin with, this circuit is not sheathed in much myelin, so every signal that goes through it leaks a lot. Each time the circuit is used, more myelin is deposited around it so that over time and repeated use, the circuit becomes sheathed in a thick layer of myelin—enabling a clear, strong signal every time, like in a wire connecting two points with thick insulation.

And that's how you create a new habit!

Cultivating New Habits

Think of the habit as a flywheel. You want to maximise the flywheel's rotational energy until it becomes 'automatic.' When the flywheel's rotational energy changes, it creates a new 'set point'.

Think of your willpower as a motor connected to that flywheel. Every time you use your willpower positively, it drives the flywheel a bit harder, and then you can switch off the motor for a while and do other things with your attention. If you use your 'willpower motor' negatively, it actively slows down the momentum of your flywheel, and the habit becomes weaker. Every time you use your willpower, you generate a new layer of myelin in the pathway in your brain that is encoding the habit.

The goal is to use the motor to speed up the flywheel to the point where it becomes self-sustaining, creating a highly insulated circuit in your brain to encode the habit and create a new set point and habit. To do this:

Repeat the activity at a constant periodicity.

Use a reminder mechanism to remind you - e.g. a Calendar app or a particular stimuli, and if needed, a mechanism to ‘punish’ you for not doing the activity - e.g. a commitment you make to someone else.

Build a positive reward for yourself every time you repeat the activity.

Try to build and record a 'streak' - if you have built a streak of working out for 20 days, then it is so much easier on day 21 - it is 'automatic'.

To create enough of a circuit to have the beginning of a habit - try to build a streak of at least 20 repetitions. When you have made 500 repetitions, the circuit is engraved in your brain.

Adhering to these principles can kickstart habits and propel them toward autonomy.

Maintaining Habits

Once a habit flywheel has strong momentum, and you have a robust, highly insulated mental circuit to encode the habit, it needs just a little repetition to maintain. The stronger the original habit, the longer it will take for the flywheel to slow down to zero or the myelin to be redistributed in your brain to create a new pathway. The good news is that as long as you occasionally repeat the habit, it is easy to rebuild it with repetition.

Breaking Habits

You can use the framework to create, strengthen, and break a habit.

If you want to stop doing something, use your willpower to consciously take the decision NOT to do it multiple times - and reward yourself with something else each time. Then, use your willpower not to 'break the streak'. Substituting a different habit which is closely related can also 'switch' the formed circuit over to the new habit and make it easier to break the old habit. For example, if you are addicted to looking at your phone every 30 seconds, try and create an alternate habit - for example, consciously taking a deep breath whenever you feel the urge to look at the phone. This will be difficult, but over time, you can replace bad habits with good ones by 'taking over' the neural circuitry already formed.

Using the framework

This framework is a way to program your brain consciously.

It can be used in the physical and mental areas of your personal life and multiple regions of your work life.

The broader idea is that most things have set points, and there is inertia around these.

Use your willpower occasionally to drive the flywheel and continue its momentum while you can focus elsewhere. This useful concept allows you to juggle things—run them in parallel, multitask, and set a project in motion, anticipating the next time you need to focus again.

Further reading and sources

Hiking trails are similar to your brain pathways. Just as a grassy path becomes flattened, matted and worn away every time a hiker walks over it, as you focus on something with your thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, you strengthen your brain pathways. Over the days, months and years, a well-traveled hiking trail becomes a well-worn pathway. Compare this to a trail that is not well-travelled or perhaps a faint trail made by small animals. These trails might be noticeable to the naked eye, however their visibility pales in comparison to the trails that get higher foot traffic.

This is great news for making desired changes. As long as you know how to develop and strengthen neural pathways, you can change just about anything you want. This is also why the habits you have had for many years are the most challenging to change. They have carved the most well-worn grooves, or deepest trails, in your brain. Thus, the pathway related to getting dressed in the morning at 50 years old is much deeper and worn than the pathway you had at 8 years old.

https://www.authenticityassociates.com/neural-plasticity-4-steps-to-change-your-brain/

Myelin is a sausage-shaped layer of dense fat that wraps around the nerve fibers — and that its seeming dullness is, in fact, exactly the point. Myelin works the same way that rubber insulation works on a wire, keeping the signal strong by preventing electrical impulses from leaking out. This myelin sheath is, basically, electrical tape, which is one reason that myelin, along with its associated cells, was classified as glia (Greek for "glue"). Its very inertness is why the first brain researchers named their new science after the neuron instead of its insulation. They were correct to do so: neurons can indeed explain almost every class of mental phenomenon—memory, emotion, muscle control, sensory perception and so on. But there's one question neurons can't explain: why does it take so long to learn complex skills?

"Everything neurons do, they do pretty quickly; it happens with the flick of a switch," Fields said. "But flicking switches is not how we learn a lot of things. Getting good at piano or chess or baseball takes a lot of time, and that's what myelin is good at."

To the surprise of many neurologists, it turns out this electrical tape is quietly interacting with the neurons. Through a mechanism that Fields and his research team described in a 2006 paper in the journal Neuron, the little sausages of myelin get thicker when the nerve is repeatedly stimulated. The thicker the myelin gets, the better it insulates, and the faster and more accurately the signals travel. As Fields puts it, "The signals have to travel at the right speed, arrive at the right time, and myelination is the brain's way of controlling that speed." 2

It adds up to a two-part dynamic that is elegant enough to please Darwin himself: myelin controls the impulse speed, and impulse speed is crucial. The better we can control it, the better we can control the timing of our thoughts and movements, whether we're running, reading, singing or, perhaps more to the point, hitting a wicked topspin backhand.

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/04/sports/playmagazine/04play-talent.html?_r=0

What do good athletes do when they train?" George Bartzokis, a professor of neurology at U.C.L.A., had told me. "They send precise impulses along wires that give the signal to myelinate that wire. They end up, after all the training, with a super-duper wire — lots of bandwidth, high-speed T-1 line. That's what makes them different from the rest of us."

The Handbook" distills its lesson to a formula known as the Power Law of Learning: T = a P-b . (Don't ask.) A slightly more useful translation: Deliberate practice means working on technique, seeking constant critical feedback and focusing ruthlessly on improving weaknesses.

https://www.lifehack.org/articles/featured/18-tricks-to-make-new-habits-stick.html

https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/1835-energy-requirements-of-the-body

Love how you broke this down so clearly that I’ll probably remember the motor and flywheel analogy forever. Thank you!

As always good read Adi. thanks for sharing. definitely gonna apply this into daily life to build habits.